The Biology and Management of the Avocado Thrips, Scirtothrips perseae Nakahara (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)

Prepared by Mark Hoddle, Extension Specialist and Director of Center for Invasive Species Research

mark.hoddle@ucr.edu

Overview of Thrips |

|

Figure 1. An adult avocado thrips (Scirtothrips perseae Nakahara) |

Historical review. The major thrips pest attacking avocados in California is the avocado thrips, Scirtothrips perseae Nakahara (Fig. 1). At time of discovery this insect was a species new to science and its country of origin was unknown. This insect was first noticed in California in July 1996 when it was discovered damaging fruit in a Saticoy avocado orchard in Ventura County. Since this initial discovery the thrips population increased rapidly causing significant damage to foliage and fruit in Ventura. In little under a year the thrips spread north and south of Ventura and was found in San Diego County in May 1997. By July 1997 significant damage attributable to avocado thrips feeding was noticed in orchards in San Diego County. In 1971, a quarantine interception at the Port of San Diego resulted in the collection of a single female specimen of an undescribed species of Scirtothrips on avocado plants from Oaxaca in southern Mexico. This single specimen is very similar to avocado thrips. Avocado thrips is not an avocado adapted strain of citrus thrips, Scirtothrips citri. Avocado thrips is morphologically more similar to Scirtothrips aceri found on oaks in California and Arizona and Scirtothrips abditus which inhabits pines and oaks in Mexico and Costa Rica.

Thrips overview. Thrips belong to the insect order Thysanoptera which means fringe wings (the wings of adult thrips are fringed with long hairs) and 5,000 species of thrips are known of which just 1% are pests. Thrips is a Latin word derived from the Greek for wood louse, and is used in both the singular and plural. Thrip is not a correct term. Thrips are typically small, slender bodied insects around 0.5-15 mm in length. Although winged, thrips are poor fliers but can be transported long distances by winds and storm fronts. The majority of thrips feed on plant juices. Some species are predators, others feed on pollen, fungi, decaying vegetation, or are omnivorous. Thrips have unusual mouthparts in that they only have one mandible. This single mandible is used like a needle to puncture plant tissue from which food and liquids are siphoned into the mouth through a straw like structure which is formed from moveable appendages around the mouth.

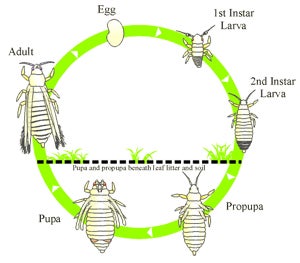

| Diagram A. Generalized Scirtothrips lifecycle |

Thrips lifecycle. Female Scirtothrips lay eggs singly in an incision made into soft plant tissue with the ovipositor and eggs are kidney shaped and whitish-yellow in color. In contrast, some species of predatory thrips lay eggs on leaf surfaces (e.g., black hunter thrips [Leptothrips spp.]). Following egg hatch, developing thrips pass through two actively feeding immature stages called larvae. All thrips species have more than one pupal stage. The first Scirtothrips pupal stage is the propupa and the second is the pupa. Thrips do not feed as pupae and many drop into the soil and leaf litter below host plants to pupate. Following pupation adult thrips move back onto the host plant to commence feeding and reproduction. A generalized Scirtothrips lifecycle is shown in Diagram A (English) (Spanish).

Pest identification. An important step in any pest management program is the accurate identification of the pest. This is particularly true for biological control because natural enemies are often specific to just one pest or group of pests e.g., thrips. In California three thrips species are commonly found on avocados, these being: (1) western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis), (2) greenhouse thrips (Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis), and (3) avocado thrips (Scirtothrips perseae).

| Figure 2. An Adult Western Flower Thrips | Figure 3. Dark Brown Western Flower Thrips | Figure 4. Male Western Flower Thrips |

Western flower thrips. Western flower thrips is commonly found in flowers of a wide variety of plants in California. Adults feed on flowers and females lay eggs within flowers and immature thrips feed here until development is completed. Although extremely high numbers of western flower thrips can be found in avocado flowers this insect is not a pest during bloom periods and does not cause significant damage to avocado foliage. Adult females of western flower thrips range in color from light yellow (Fig. 2) to dark brown (Fig. 3). Males are smaller and uniformly yellow in color (Fig. 4). Dark colored bands that run across the abdomen appear similar to those on avocado thrips. Both sexes of western flower thrips have stout bristle like hairs that protrude beyond the tip of the abdomen and these hairs can be seen with a hand lens. Avocado thrips lacks these obvious stout bristles on the tip of the abdomen. Western flower thrips can supplement their diet with mites. Western flower thrips is native to the western United States.

| Figure 5. Female Western Flower Thrips |

Greenhouse thrips. Greenhouse thrips is a serious pest in some coastal avocado orchards. Severe infestations have occurred in Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Diego Counties where the marine influence provides optimal temperature and humidity ranges for survivorship and population growth. On green fruit avocado varieties like Bacon and Zutano, greenhouse thrips feed primarily on foliage. On Hass avocados young fruit is preferred. Greenhouse thrips feed gregariously and populations are generally higher on plants where fruit contact each other as this provides protection and ideal micro-climates for greenhouse thrips. This species produces female offspring without mating and males are rare in the population. Females are black in color and have white wings which lie beside each other and cover the thorax and abdomen at rest (Fig. 5). Females insert eggs into young fruit and foliage and larvae produce globules of fecal material at the tip of the abdomen. Globules increase in size until they are shed and another begins to form. Fecal globules are a defense against natural enemies. Larvae and adults are sluggish and adults rarely fly. Greenhouse thrips has a worldwide distribution.

| Figure 6. Avocado fruit shows damage from Thrips |

Avocado thrips. Avocado thrips are unusual amongst thrips in that adult and immature stages are readily observed on upper leaf surfaces. When disturbed they run to leaf edges and move to the leaf's under surface. Thrips larvae are most commonly found on the underside of leaves. Males and females are present in the population and males are the smaller of the two sexes. Adults are straw yellow in color, and have thin dark lines running across the upper surface of the abdomen. The wings are brown in color when folded on top of the abdomen (Fig. 1). Larvae are pale yellow in color. Feeding damage to foliage is observed on upper and lower leaf surfaces and bronze colored damage initially follows leaf veins. As the thrips population and feeding damage increases bronzing is observed in random patterns between leaf veins (Fig. 6). Avocado thrips larvae and adults feed on developing fruit while hidden under the calyx. Fruit is susceptible to damage until it exceeds the size of a half dollar. Feeding scars develop from the calyx and as feeding continues scars radiate towards the top of fruit (Fig. 7). Fruit scarring can be severe resulting in "alligator skin". Avocado thrips has only been found feeding on avocado. In greenhouse experiments, avocado thrips has been observed feeding on young foliage of Hass, Lamb Hass, Zutano, Bacon, Lulu, and Topa-Topa.

Biology of Avocado Thrips |

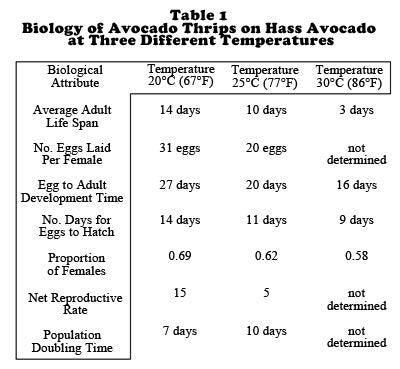

The developmental and reproductive biology of avocado thrips has been studied in the laboratory and is shown in Table 1. Females lay eggs in young fruit, fruit petioles and the undersides of young leaves. Eggs are not laid in leaf petioles or young green stems. Larvae pupate in leaf duff under trees, in cracks and crevices in the bark, or within persea mite nests on leaves. Surveys of leaf duff indicate that 89% of pupating thrips are found in the uppermost undecomposed layers of leaves. The partially decompsed leaf litter below the upper layer of undecomposed leaves harbors 10% of pupating thrips, while the soil provides refuge for just 1% of thrips pupae. Second instar larvae and females are probably the most damaging stage as they feed more than first instars, pupae and males.

Temperature and avocado thrips population declines. Avocado thrips is unusual with respect to other pest species of Scirtothrips as it outbreaks over winter and spring when temperatures are low. Scirtothrips citri (the California citrus thrips), S. aurantii (the South African citrus thrips) and S. dorsalis (the chilli thrips) reach damaging densities over summer in countries in which they are problematic. Laboratory studies have indicated that as temperatures increase from 20°C to 25°C population growth rates for avocado thrips are reduced by 33%. Population declines have been observed for avocado thrips over summer in orchards where young leaves that are suitable for feeding and oviposition are abundant. This strongly suggests that high temperatures are probably responsible for population crashes. The exact temperature regimen needed to cause declines of avocado thrips in orchards is currently unknown. It is highly likely that several consecutive days with temperatures within the tree canopy exceeding 30°C (86°F) for several hours and low humidity (<50%) are necessary. Population declines will not occur immediately after summer heatwaves and there are several reasons for this. First, avocado thrips are highly mobile and will locate cool microclimates within orchards to escape the heat. Second, temperatures are not a constant 30°C for the entire day and cool mornings and nights reduce the duration of heat stress experienced by avocado thrips. Third, temperatures recorded on the orchard floor can be several degrees higher than those experienced by avocado thrips as they feed on transpiring leaves. The majority of fruit damage occurs in spring when fruit are still small and highly susceptible to thrips feeding. Heatwaves at this time can not be relied upon to reduce avocado thrips densities to low non-damaging levels.

| Figure 7. Mark Hoddle sampling for avocado thrips in Ayutla, Oaxaca. |

Area of origin for the avocado thrips. Foreign exploration for avocado thrips and its natural enemies in Latin America has delineated a geographic distribution for this pest ranging from Mexico City to Guatemala City. Avocado thrips has been readily found on young avocado foliage on roadside trees, back yard plants, and in abandoned orchards (see sampling for avocado thrips in Ayutla, Oaxaca). This pest has been found in lower densities in heavily sprayed commercial orchards in Mexico and Guatemala. The most common natural enemies associated with avocado thrips in Latin America have been predacious thrips in the genera Leptothrips (Phlaeothripidae) and Franklinothrips (Aeolothripidae). Thrips parasitoids in the genus Ceranisus (Hymenopterea: Eulophidae) have been found also. Lacewing larvae (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) and pirate bugs (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) are not commonly found with avocado thrips in Latin America or California.

Distinguishing western flower thrips from avocado thrips. The majority of western flower thrips larvae and adults are

found in avocado flowers and disperse after flowering is completed. Avocado thrips larvae and adults are predominantly found feeding under the calyxes of small fruit and on the upper and lower surfaces of young leaves. Western flower thrips larvae are slender, cigar shaped, white to pale yellow in color, slow moving and have stout hairs towards the end of the abdomen that can be seen with a hand lens. Avocado thrips larvae, on the other hand, are oval in shape, yellow to amber in color, are quite active, and have barely visible abdominal hairs. Adult avocado thrips are straw yellow in color, have fine brown-black lines running across the abdomen, and are very active. Western flower thrips adults are yellow-brown in color, are larger and more sluggish in comparison to avocado thrips, and have obvious hairs at the end of the abdomen which adult avocado thrips lack (Fig. 8). The best way to distinguish between these two thrips is to collect western flower thrips from flowers and with a hand lens compare them to avocado thrips.

Natural Enemies of Thrips |

A high diversity of thrips natural enemies exist in avocado orchards. Although the impact of this fauna against avocado thrips is unknown, it is advisable whenever possible to conserve predators and parasitoids by applying pesticides only when absolutely necessary. To assist with avocado thrips management decisions a guide to identifying commonly encountered thrips natural enemies is provided.

|

Figure 9. Pirate bug adult. |

Thrips Predators

Thrips are eaten by many generalist predators which are found in avocado orchards. Readily identifiable thrips predators and are listed below.

Pirate Bugs. (Fig. 9) Pirate bugs in the genus Orius are sold commercially for thrips control and are commonly encountered in a variety of outdoor agricultural crops where they attack mites and thrips (plant eating thrips and predatory thrips are attacked by Orius). Host plants can have an important effect on the number of thrips killed by pirate bugs and whether pirate bugs can reproduce on the host plant. For example, pirate bugs are ineffective natural enemies for thrips on tomatoes because they can not reproduce on this plant, while hairy leaves on some cucumber varieties impede pirate bug searching. Pirate bugs are seldom observed in association with avocado thrips in California and may not be important natural enemies of this pest.

|

Figure 10. Lacewing Larva |

Lacewings. Lacewing larvae (Fig. 10) are voracious thrips predators that are commonly found in avocado orchards. Lacewings are commercially available and can be purchased as eggs or larvae and applied to plants by hand. In the laboratory the lacewing Chrysoperla rufilabris can consume 100 second instar citrus thrips (Scirtothrips citri) larvae or 80 citrus thrips adults during its first larval instar and 324 2nd instar citrus thrips larvae or 277 adults during its second larval instar. On potted plants in cages, C. carnea and C. rufilabris caused 82.5% and 77.1% mortality of citrus thrips respectively when compared to plants that were not treated with lacewings. Lacewing releases into citrus orchards significantly reduced fruit damage caused by citrus thrips on plants that were treated with lacewings when compared to plants that did not receive lacewings. Similar research with lacewings for biological control of avocado thrips is planned. Lacewing adults are not predatory and sustain themselves by feeding on honeydew or nectar.

| Figure 11. Franklinothrips vespiformis adult, a predatory thrips that preys on avocado thrips. |

Predatory thrips. Evidence from field experiments suggests that most predatory thrips are unable to control pest thrips on their own because they breed too slowly and lay fewer eggs than their prey. Franklinothrips vespiformis (Fig. 11) is being mass reared by Koppert Biologicals in the Netherlands and this predator may soon be commercially available. Seasonal inocualtive releases of F. vespiformis in early spring may provide indigenous populations with a boost and provide suppression of avocado thrips before this pest reaches economically injurious levels. Predatory thrips are the most important naturally occurring component of the generalist predator fauna attacking avocado thrips.

Predatory mites. The most common predatory mite found in avocado orchards is the phytoseiid Euseius hibisci. This predator is common in orchards year-round, and attacks plant feeding mites, thrips, and supplements its diet with pollen and plant juice. The impact of Euseius hibisci on avocado thrips is unknown but the closely related Euseius tularensis is an effective predator of citrus thrips. Experimental results have shown that E. tularensis can substantially reduce fruit damage caused by citrus thrips.

Parasitic Wasps

| Figure 12. Ceranisus menes, a parasitic wasp found in avocado orchards. |

Two parasitic wasps found in avocado orchards that parasitize thrips larvae are Thripobius semiluteus and Ceranisus menes (Fig. 12). Thrips parasitoids lay their eggs inside the body cavity of thrips larvae and developing parasitoids feed internally killing the host. Wasp larvae pupate inside dead thrips and emerge as adults. Thrips parasitized by Thripobius turn black and have a mummified appearance (Fig 5). Thripobius significantly reduces fruit scarring by greenhouse thrips when parasitism reaches 60% or more. It is unknown if Thripobius will parasitize avocado thrips. A trichogrammatid parasitoid, Megaphragma mymaripenne, is common in avocado orchards and parasitizes thrips eggs but does not provide effective thrips control on its own. Thrips parasitoids may be a valuable element of the natural enemy fauna attacking avocado thrips, but at this time nothing is known about their impact on avocado thrips.

Spraying for Thrips and Conserving Natural Enemies |

To reduce the likelihood of resurgence (recovery of pest populations, sometimes to levels higher than before treatments began) and secondary pest outbreaks (release of non-pest insects from biological control due to natural enemy mortality from pesticides) it is necessary to use insecticides that are compatible with natural enemies and to provide refuges for biological control agents. Compatible insecticides have short residual activity or are non-toxic to natural enemies. The botanical insecticide sabadilla is compatible with natural enemies because it has short residual activity and is not toxic to natural enemies. Biological control agents can be protected in refuges. Untreated trees provide refuges for natural enemies allowing them to recolonize sprayed areas. Natural enemies can be purchased to re-inoculate orchards after insecticide treatments have been made or to augment the orchard’s indigenous natural enemy fauna (see Hunter 1994 for suppliers of beneficial insects).

Frequent use of a limited number of insecticides with similar modes of action (e.g., stomach poisons) can result in insecticide resistance. Insecticide resistance is the developed ability of an insect population to withstand insecticides that were formerly effective. The rate at which resistance develops in a population is related to intensity of insecticide use. To prolong insecticide efficacy for avocado thrips, it is advisable to limit frequency of applications by spraying only when necessary, to alternate between insecticides with different modes of action, and to leave areas of the orchard untreated (this will conserve natural enemies and allow survival of susceptible thrips that can breed with thrips with resistance genes thereby reducing the rate at which insecticide resistance develops).

Recommendations for insecticidal control of avocado thrips will improve as knowledge on biology and phenology of avocado thrips and its natural enemies increases, when key natural enemies are screened for susceptibility to registered insecticides, and as results of insecticide field trials are analyzed.

Agri-Mek. Agri-Mek is an insecticide and miticide containing the active ingredient abamectin. Abamectin is produced by a soil dwelling bacteria Streptomyces avermitilis. Abamectin is a mixture of avermectins containing 80% avermectin B1a and 20% avermectin B1b. Agri-Mek suppresses insect feeding by activating chloride ion conductance in the nervous system which is mediated by the inhibitory neurotransmitter gama-aminobutyric acid (GABA). This results in paralysis of susceptible pests, and causes cessation of feeding, and eventual death from starvation. Pests immobilized after ingesting Agri-Mek may take several days to die. During this time pests are not feeding or damaging plants. Consquently, care must be taken when assessing the effectiveness of applications. With proper application Agri-Mek penetrates leaf tissue and forms a reservoir of active ingredient within the leaf. This reservoir provides residual activity against foliage feeding pests. Surface residues of Agri-Mek are rapidly degraded in sunlight and as a consequence little residual activity against natural enemies is observed. Contact toxicity by Agri-Mek has been observed in some circumstances. Agri-Mek that runs off leaves into the soil is rapidly degraded by soil micro-organisms and this toxin does not appear to bioaccumulate in the environment.

Agri-Mek and Section 18 regulations. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the California Department of Pesticide Regulations (CDPR) have approved Agri-Mek for use in California avocado orchards against avocado thrips. The Section 18 allows for statewide use of Agri-Mek and applications can be made by air or ground. The pre-harvest interval for Agri-Mek (i.e., the time from last spray to harvesting) is 14 days (effective March 25, 1999). Growers must contact their local Agricultural Commissioner to obtain a restricted materials permit prior to using Agri-Mek. To be eligible for restricted materials permit the Agricultural Commissioner needs to be provided with the following:

- A map of the orchard with building locations indicated.

- The maximum number of acres that are expected to be treated.

- The maximum amount of Agri-Mek that is to be applied to the orchard.

- The name of the distributor supplying Agri-Mek for anticipated treatments.

- The location of water sources within the orchard.

- A grower indentification number which can be assigned by the County Agricultural Commissioner.

A copy of the Section 18 label must be on the property and immediately available to the person applying Agri-Mek. Applicaton of Agri-Mek must be made by, or under the supervision of an applicator certified for this category of pest control. After applications are made the re-entry interval is 12 hours.

Agri-Mek and potential impact on bees and non-target wildlife. Agri-Mek is toxic to bees but folair residues dissipate quickly making this insecticide essentially non-toxic to bees as a foliar residue after a few hours. If bee hives are present in orchards bee keepers need to be notified so hives can be removed before Agri-Mek is applied. If hives can not be removed from the orchard they can be covered to keep bees within hives or sprays can be made early in the morning while it is too cold for bees to fly. Do not apply Agri-Mek to blooming avocados. Agri-Mek is toxic to fish, aquatic organisms and wildlife. Sprays should not be applied directly to water or wetlands (e.g., bogs, marshes, and potholes). Agri-Mek should not be applied if weather conditions threaten to carry spray drift to sensitive aquatic areas.

Additional Information |

For further information on biological control and research on avocado thrips contact:

- Mark Hoddle, Dept. of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, phone: (951) 827-4714, fax: (951) 827-3086, mark.hoddle@ucr.edu

- Ben Faber, Cooperative Extension, Ventura County, 669 County Square Drive, Ste. 100, Ventura, CA 93001, phone: (805) 645-1462, fax: (805) 645-1474, bafaber@ucdavis.edu

- Gary Bender, UCCE Office, 5555 Overland Ave, Bldg 4, San Deigo, CA 92123, phone: (619) 694-2848, fax: (619) 694-2856, gsbender@ucdavis.edu

- Joseph Morse, Dept. of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, phone: (951) 827-5814, fax no. (951) 827-3086, joseph.morse@ucr.edu

A free factsheet on the biology and managment of the avocado thrips is available from the California Avocado Commission by calling 949-341-1955 or by requesting it directly from their website.

Acknowledgments. Photographs used in this factsheet were taken by: Mr. Jack Kelly Clark (UC Photographer), Michael Parrella, Margaret Skinner, and Karsten Drescher. Avocado thrips life cycle schematic was prepared by Dr. Vincent D'Amico III (Bean's Art Ink, CT). Preparation of this web page was supported in part by the California Avocado Commission.

References |

- Hoddle, M.S. and Morse, J.G. 1997. Avocado thrips: a serious new pest of avocados in California. California Avocado Society Yearbook 81: 81-90.

- Hoddle, M.S. 1998. What we know about avocado thrips. California Grower 22: 17-19.

- Hoddle, M.S. and Morse, J.G. 1998. Avocado thrips update. Citrograph 83: 3-7.

- Hoddle, M.S., Morse, J.G., Phillips, P. and Faber, B. 1998. Progress on the management of avocado thrips. California Avocado Society Yearbook 82: 87-100.

- Hoddle, M.S., Morse, J.G., Phillips, P., Faber, B., Yee, W., and Peirce, S. 1999. Avocado thrips update. Citrograph 84: 13-14.

- Hoddle, M.S., Morse, J.G., Phillips, P., Faber, B., Yee, W., and Peirce, S. 1999. Avocado thrips update. California Grower 23: 22-24.

- Hoddle, M.S., Robinson, L., Drescher, K. and Jones, J. 2000. Developmental and reproductive biology of a predatory Franklinothrips n. sp. (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae). Biological Control 18: 27-38.

- Hunter C.D. 1997. Suppliers of beneficial organisms in north America. Copies are available from California Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Pesticide Regulation, Environmental Monitoring and Pest Management Branch, 1020 N Street, Room 161, Sacremento, California 95814-5604, phone no. (916) 324-4100. This booklet is electronically available Natural Enemy Supplier Handbook

- Lewis T. 1973. Thrips: their biology, ecology, and economic importance. Academic Press, London. 349 pp.

- Parker, B.L., Skinner, M. & Lewis, T. (Eds) 1995. Thrips biology and management. Plenum Press, New York. 636 pp.

- Philips P. 1997. Managing greenhouse thrips in coastal avocados. Subtropical Fruit News 5: 1-3.

- UC IPM Thrips Web Page. http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn030.html (you can load the following keywords into a search engine: UC IPM Thrips Pestnotes).

- Van Driesche R.G. & Bellows T.S. Jr. 1996. Biological Control. Chapman and Hall, New York. 539 pp.