Biology and Management of South American Palm Weevil, Rhynchophorus palmarum (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in California

Prepared by Mark Hoddle

Extension Specialist in biological control

Director of the Center for Invasive Species Research

Department of Entomology,

University of California, Riverside

mark.hoddle@ucr.edu

Prepared by Ivan Milosavljević

Supervisory Project Scientist

Department of Entomology,

University of California, Riverside

ivanm@ucr.edu

Introduction

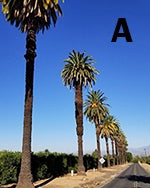

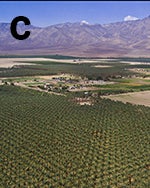

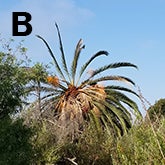

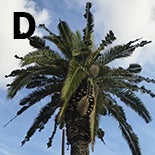

| Plantings of (A) ornamental Canary Islands date palms and (B) ornamental edible date palms define California’s urban landscape and are threatened by SAPW. (C) Edible date garden in Coachella Valley | ||

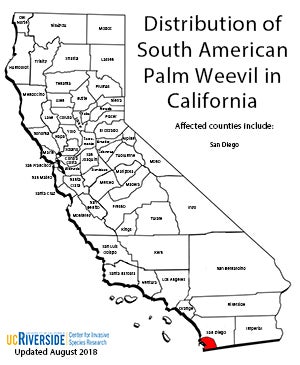

South American palm weevil (SAPW), Rhynchophorus palmarum (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), is native to parts of Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. SAPW is an invasive pest in California. It was first collected from infested Canary Islands date palms (Phoenix canariensis) in Tijuana Baja California Mexico in 2010. Weevils were later captured in monitoring traps in San Ysidro in southern San Diego County in 2011 (~ 5 miles north of Tijuana). Weevil populations likely established in or around San Ysidro in 2014 or earlier. This weevil presents an enormous threat to the ornamental and edible date palm industries in California. The urban landscape in California is defined by palms, especially the ubiquitous Canary Islands date palm (Phoenix canariensis) and edible date palm (Phoenix dactylifera). Some estimates suggest that the ornamental palm industry in California is worth ~$70 million (US) per year. Canary Islands date palms have been valued at $500 (US) per 12 inch lengths of trunk and individual “mature” ornamental edible date palms cost around $5,000 (US). The edible date industry in Coachella Valley is worth about $68 million (US), produces approximately 47,000 tons of fruit, employs around 6,000 people, and is grown on about 10,000 acres. In addition to detections in San Ysidro (Bech 2011), R. palmarum was also detected in Alamo Texas in March and May 2012 (El-Lissy 2012), and Yuma Arizona in May 2015 (El-Lissy 2015). There are no reports of established populations of R. palmarum in Arizona and Texas or palm mortality caused by this weevil.

Host Plants

SAPW is a notorious palm pest in its native and invaded ranges. It has been recorded attacking and reproducing on the following palm species: coconut (Cocos nucifera), African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), açaí palm (Euterpe oleracea), coco de palmito(Euterpe edulis), sago palm(Metroxylon sagu), Canary Islands date palm (Phoenix canariensis), and edible date palm (Phoenix dactylifera). SAPW will also complete development on field planted sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum). Adult weevils have been recorded feeding on ripe fruit of non-palm hosts, including avocados (Persea americana), pineapple (Ananas comosus), custard apple (Annona reticulata), breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis), papaya (Carica papaya), citrus (Citrus spp.), mango (Mangifera indica), banana (Musa spp.), guava (Psidium guajava), and cocoa (Theobroma cacao). SAPW cannot reproduce on these fruit. In the lab, colonies of adult weevils can be maintained for 2-3 months on a mixed diet of cut apples and bananas (with the skin left on), and split sugar cane.

| Drone surveillance of Canary Islands date palms killed by SAPW in the Sweetwater Reserve, Bonita California |

Palm Damage

Damage to palm trees results primarily from larval feeding that is concentrated in the apical meristem or the palm heart. This relatively soft and fleshy growing material is typically found in the crown or top part of the palm tree, and it is responsible for generating new fronds. Heavy larval infestations in this region can result in crown collapse and palm mortality. Occasionally, meristematic tissue may occur near the base of the trunk where offshoots grow. Feeding in this region can lead to trunk collapse and palm death.

High levels of feeding damage to the apical meristem can result in palm death as frond and trunk growth originates from this region. Highly damaged areas take on a characteristic appearance as the crown tilts, collapses, and dies. Palms in the advanced stages of attack and mortality have a flattened top, and as the remaining halo of fronds that ring the top of the trunk dry down, the palm looks like a giant brown umbrella or mushroom.

In some instances the top of the palm may drop to the ground because it becomes detached from the top of the trunk because internal feeding by larvae is so severe.

| (A) A dropped Canary Islands date palm crown that rolled down the street after being killed by SAPW. (B) Dropped Canary Islands date palm crown in a reserve in San Diego County | |

Heavily infested palms will drop fronds the bases of which may be heavily tunneled indicating larval feeding and pupation activity. Basal sheaths, a fibrous material found at the base of the palm fronds, will have holes caused by weevil larvae that have tunneled into the frond bases. Occasionally, pupal cases will drop from heavily infested palms and accumulations on the ground can be observed. Many of these cocoons may be empty as the adult weevils have emerged. Unemerged adult weevils, pre-pupal larvae, and pupae may be found if dropped cocoons collected from the ground are opened.

Fronds damaged by weevil feeding during the early stages of development as they are pushing up from the apical meristematic bulb appear “notched” or to have windows. This damage can be confused with feeding by rats.

|

Canary Islands date palms showing various levels of feeding damage caused by SAPW |

|||

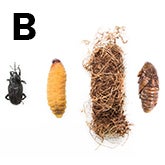

Life Cycle

Male weevils release an aggregation pheromone, rhynchophorol, (2E)-6-methyl-2-hepten-4-ol, which attracts male and female weevils to suitable hosts. Female weevils use their rostrum or snout (this is the long “nose” on the head of the weevil) to drill holes into palm material. Eggs are laid in these “holes,” they are relatively large, and female weevils can probably lay a hundred eggs or more over the course of a life time. Females may also lay eggs into cracks or wounds on the trunk or the base of the fronds. Weevil larvae hatch from eggs and consume meristematic tissue. Mature weevil larvae may reach up to five inches in length prior to pupating. Feeding larvae cause significant damage to the apical meristem and when severe, palm death can result. As the infestation progresses, damaged palm material inside the palm will start fermenting and it acquires a characteristic odor. This fermenting “mush” is noticeably warm and very wet, and being inside the palm trunk these conditions may mitigate adverse environmental conditions such as low humidity and temperature. These fermentation odors (especially when coupled with aggregation pheromone) from feeding and other types of damage (e.g., pruning wounds or pathogen infections) attract weevils to palms which intensifies attacks.

|

(A) The top of a male SAPW rostrum showing the dense comb of setae that characterizes this sex. (B) The top side of the female rostrum lacks setae which makes distinguishing between sexes easy to do |

|

Prepupal larvae spin surprisingly tough cocoons from palm fibers and cocoon construction often occurs in tunnels at the base of fronds. Cocoons tend to be wedged tightly in these tunnels and can be hard to extract. The prepupal larva molts inside the cocoon and develops wing buds. The pupa will molt one more time within the cocoon to reach the adult form which has wings and can fly. The entire life cycle, egg to adult, can take about 3-4 months to complete.

Adult SAPW use their mandibles (i.e., “teeth”) at the end of the rostrum to chew their way out of the cocoon, they are typically black, and live for 1-2 months. A small percentage of the adult population may have orange and black markings that are very similar to another notorious palm pest, the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. These orange and black morphs of SAPW have been found in California.

Adult weevils are sexually dimorphic. Males can be separated from females by the presence of a “beard” or “comb” of hairs (i.e., setae) on the dorsal (i.e., top) side of the rostrum. Females lack these setae and the top of the rostrum is smooth. Adult weevils can be found wedged into cracks at the base of palm fronds.

Dispersal

Adult SAPW are strong fliers and have the potential to disperse naturally over long distances. In the lab, flight mill studies indicate that male and female weevils are capable of flying over 15 miles a day or more if they chose to do so. It is unknown if weevils undertake such long distance flights in nature. However, flight mill studies indicate it is possible should weevils elect to do so and this could occur in areas where there are no suitable hosts to attack. In nature, adult weevils tend to fly during daylight hours and some studies suggest that they may only fly 1 mile over the course of a day. Weevils can potentially be moved accidentally by humans over long distances inside infested palms. Movement of live ornamental palms out of infested areas should be avoided to reduce the chances of unintended weevil introductions into new areas.

Trapping and Monitoring

Adult weevils are attracted to traps loaded with commercially-available aggregation pheromone and baited with fermenting fruit. Ethyl acetate (i.e., available as nail polish remover, check ingredients listing) can be used as a synergist to increase the combined attractiveness of the pheromone and bait.

There are two basic types of weevil trap, the bucket trap and the pyramid shaped Picusan trap. Bucket traps can be suspended above the ground or partially buried. Picusan traps are designed to be placed on the ground but they can be suspended.

Details on making bucket traps and loading them with aggregation pheromone, ethyl acetate synergist, and fermenting bait are available.

Trap placement is important for detecting weevil activity in an area of concern. Studies on red palm weevil in Europe have contributed to the following recommendations for trap placement for SAPW in California. Traps should not be hung from palm trees or placed near (i.e., within 500 yards) palms of interest. Traps are not 100% efficient in capturing weevils. If traps are placed too close to palms adults that are attracted to traps but are not caught may start infestations in the palm that is being monitored. If detecting low levels of palm weevil activity in the general vicinity is the goal of the monitoring program, traps should be deployed outside (perhaps > 0.5 mile away) of the immediate area of concern. If weevils are captured at this distance from the palms of concern it likely indicates that weevil activity is close and steps should be promptly considered and implemented for protecting those palms. Trap efficacy is maximized if traps are placed in areas with partial or full shade. Full sun exposure, especially during the hottest parts of the day, rapidly diminishes trap potency.

Chemical Control

Systemic pesticides are at present the most effective tool available for protecting and potentially curing palms of SAPW infestations. Systemic pesticides (mainly neonicotinoids) are translocated within the palm and accumulate in the meristematic tissue where weevil larvae feed. Systemic pesticides can be applied as soil drenches, soil injections, trunk sprays or paints, trunk injections, or as drenches applied to the crown. Contact insecticides (i.e., pesticides that either kill on contact or leave a dry external residue that is lethal upon contact) can be applied to palm fronds or pruning wounds to kill adult weevils attracted to these substrates. Developing a pesticide treatment program should be made in consultation with a professional arborist, and two or more applications per year may be needed in infested areas to protect palms from weevil attack. Systemic pesticides applied as crown drenches can “cure” heavily infested palms allowing meristematic tissue to recover and new frond production results.

Efficacy of pesticide treatments on weevil activity in the crown can be checked via a “window.” A window is created by removing palm fronds in the crown which then permits access to the crown so visual inspections for weevil activity can be conducted.

Biological Control of SAPW

Classical biological control is the intentional introduction of a natural enemy (e.g., parasitoid, predator, or pathogen) of an invasive pest with the goal of reducing pest populations to less damaging levels in the invaded area. One potential reason, amongst several, as to why non-native organisms become pests following introduction into a new area is the lack of population regulation provided by upper-trophic level organisms (i.e., natural enemies). The “enemy-release” hypothesis is one explanation for explosive pest population growth and spread when an invasive organism establishes in a new area. Subsequent population control may result when host specific efficacious natural enemies are re-associated with the target pest via a classical biological control program.

Several natural enemies of SAPW are known, but one group of natural enemies, parasitic flies, in the genus Billaea (formerly Paratheresia) (Diptera: Tachinidae), appear to be exceptionally promising candidates for use in a classical biological control program targeting SAPW in California. These flies have a distribution that includes parts of the known range of SAPW (i.e., South America and the Caribbean.) One species, B. rhynchophorae, appears to be particularly aggressive towards SAPW in Bahia State in Brazil. Two different yearlong surveys by Brazilian scientists indicated that parasitism of SAPW larvae/pupae averaged 40% (range 18-50%) in one study and 51% (range 33-73%) in the second survey. Flies attacked immature SAPW year round with seasonal highs (Sept. – Nov) and lows (Jun – Jul) being observed. The average number of fly puparia produced per weevil host inside the SAPW pupal cocoon is around 18.

Biological control targeting SAPW with B. rhynchophorae at the very early stages of the invasion in California could potentially reduce weevil populations. Reduced population densities could slow weevil spread and economic damage.

Removal of Infested Palms

Removal of infested, dying, or dead palms is expensive, potentially dangerous and should be undertaken by professional arborists. It is recommended that infested palm material (i.e., fronds and the bulbous top of the palm) be chipped. All transported material should be covered with a tarp and disposed of at a certified landfill that buries within 24 hours (or sooner) of dumping to reduce risks of spreading adult weevils into new areas either enroute to or around the disposal site. It is not necessary to remove the entire palm trunk. SAPW larvae don’t drill deeply into the palm trunk and infestations are typically limited to the top 25% (or less) of the palm. However, the aesthetics of a dead palm trunk may encourage complete removal and stump grinding.

Red Ring Nematode

Adult SAPW can spread a plant pathogenic nematode, Bursaphelenchus cocophilus, commonly known as red ring nematode (RRN), the causative agent of red ring disease in palms. Nematodes reside within the body of adult weevils and are deposited in palms when weevils feed, defecate, or lay eggs. Weevil larvae become parasitized with nematodes and uninfected adults can acquire nematodes when they come into contact with nematode infested palms. Palms infected with RRN can die in as little as 3-4 months after infection symptoms become noticeable. RRN has not been detected in SAPW captured in California and this nematode is not known from other locations in the USA either. RRN is known from Mexico. As is the case with many invasive vector-pathogen systems in California, the vector is detected first, then normally, several years later, the pathogen is recorded. A similar situation for SAPW-RRN may eventually develop in California. Additional information and photos of RRN and red ring disease are available.

Report an Infested Palm

SAPW is spreading through urban areas in southern California and Canary Islands date palms appear to be a highly preferred host which are very susceptible to attack. To track the spread of SAPW we need the help of community scientists, interested and concerned members of the public, who are willing to take time to report SAPW infestations via the web. To report palms that may be infested with SAPW please visit this site and fill in the online document and submit it.

Additional Reading

Anon. 2012. Rhynchophorus palmarum. USDA Factsheet.

Bech, R. (2011) Detection of South American palm weevil (Rhynchophorus palmarum) in California.

El-Lissy, O. (2012) Detection of South American palm weevil (Rhynchophorus palmarum) in Texas.

El-Lissy, O. (2015) Detection of South American palm weevil (Rhynchophorus palmarum) in Arizona.

Hoddle, M.S. and C.D. Hoddle. 2017. Palmageddon: The invasion of California by the South American palm weevil is underway. CAPCA Adviser 20 (2): 40-44.

Hodel, D.R., M.A. Marika, and L.M. Ohara. 2016. The South American palm weevil – a new threat to palms in California and the Southwest. Palm Arbor 3: 1-27.

Other Media

KQED, Deep Look: A Real Alien Invasion Is Coming to a Palm Tree Near You

CISR: Has the South American Palm Weevil, Rhynchophorus palmarum, Established in Southern California?

CISR Blog: Palmageddon: Are California’s Palms about to Face the Perfect Storm?

CISR Blog: The South American Palm Weevil Invasion in San Diego County, California